Quick post to check if the WordPress app on the BlackBerry Playbook works.

Picture is of my work desk.

Quick post to check if the WordPress app on the BlackBerry Playbook works.

Picture is of my work desk.

Today, 25th Jan, is the day that Scots the world over will be celebrating our national bard, Robert Burns.

There are ample descriptions of Burns’ Suppers being held all around the world and there will be much drunken revelry, haggis quaffing and poetry reciting tonight.

The traditional Burns poems are the famous ones such as Tam O’Shanter and Address Tae A Haggis, but I wanted to quote my favourite poem; A Man’s A Man For A’ That.

Written in 1795, the poem is an appeal to common humanity but even in Burns’ day it had to be published anonymously for fear of promoting radical ideals. Burns was clearly influenced by Thomas Paine and the American Founders and it was their ideas of liberty, Equality and universal rights that shine through in this song.

It was performed at the opening of the new Scottish Parliament in 1999.

There are some fantastic renditions of the poem here.

Is there for honest Poverty

That hings his head, an’ a’ that;

The coward slave-we pass him by,

We dare be poor for a’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that.

Our toils obscure an’ a’ that,

The rank is but the guinea’s stamp,

The Man’s the gowd for a’ that.

What though on hamely fare we dine,

Wear hoddin grey, an’ a that;

Gie fools their silks, and knaves their wine;

A Man’s a Man for a’ that:

For a’ that, and a’ that,

Their tinsel show, an’ a’ that;

The honest man, tho’ e’er sae poor,

Is king o’ men for a’ that.

Ye see yon birkie, ca’d a lord,

Wha struts, an’ stares, an’ a’ that;

Tho’ hundreds worship at his word,

He’s but a coof for a’ that:

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

His ribband, star, an’ a’ that:

The man o’ independent mind

He looks an’ laughs at a’ that.

A prince can mak a belted knight,

A marquis, duke, an’ a’ that;

But an honest man’s abon his might,

Gude faith, he maunna fa’ that!

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

Their dignities an’ a’ that;

The pith o’ sense, an’ pride o’ worth,

Are higher rank than a’ that.

Then let us pray that come it may,

(As come it will for a’ that,)

That Sense and Worth, o’er a’ the earth,

Shall bear the gree, an’ a’ that.

For a’ that, an’ a’ that,

It’s coming yet for a’ that,

That Man to Man, the world o’er,

Shall brothers be for a’ that.

In this edition of the podcast we pick up from were we left off with part 1 look at the  reformation of the 1560’s and the legacy of Knox, Mary Queen of Scots and her son James VI.

reformation of the 1560’s and the legacy of Knox, Mary Queen of Scots and her son James VI.

We also cover the two Books of Discipline which set out the theological and religious behaviours expected of all Scots.

You can listen or download the Religion Part 2 podcast from here.

The house on the right Is John Knox’s house in Edinburgh.

A very happy New Year and best wishes for 2012 to Scots the world over.

To repeat a common refrain heard in Scotland at this time:

“Here’s tae us; wha’s like us? Damn few and they’re a’ deid!”

There are plenty of movies set in Scotland that claim to shed a little light on our history and on the Scots as a nation of people. Some are famous and some are little known outside of these shores.

I want to concentrate initially on one of my favourite movies – Local Hero. Released in 1983, it tells the story of an American Oilman (Peter Riegert) sent from Dallas with the object of buying up the little fishing village of Ferness and the beach around its headland. His Boss (Burt Lancaster) sends him because Riegert’s character is called McIntyre and therefore “sounds” Scottish.

Along with the company’s Scottish representative, played by a young Peter Capaldi, they arrive in the village early in the morning after having to sleep in their car due to the mist covered mountains. This set up is clearly a allusion back to the famous Brigadoon musical, in which a magical Scottish village arises out of the mist every 100 years. The movie retains many references to Brigadoon such as the American in a Scottish village, torn between the simple life and his sophisticated life back home; but whereas that film was a love story between Gene Kelly and Cyd Charisse, in Local Hero the love affair is between Mac and the landscape.

Mac arrives with a mission to buy up the land to build a refinery and believes the locals will not want to sell because of the history and beauty of the place. The locals do seem reluctant and Mac realises this might be harder than it looks, however the joke is, the locals cant wait to sell and are playing hardball to get a higher price.

I wont spoil the plot any more than I already have but the whole film resounds with wonderful characters, who populate the village. They are so well drawn and believable that they never fall into cliche.

What could be sentimental environmental mawkishness is safe in the director Bill Forsyth’s hands. The Scottish director’s previous films showed his talent at whimsy in the fantastic Comfort and Joy and the highly acclaimed Gregory’s Girl.

There is a You Tube link to the film here but you should try and get it on DVD for the best experience.

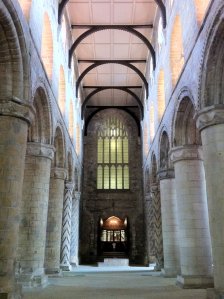

Focusing on Dunfermline as a fulcrum for the religious history of Scotland.

The story of Glencoe and the massacre of the McDonalds by the Government Campbell troops.

After introducing the Abbey and going on to discuss the rise of the religious house, we now come to the Reformation.

Its impossible to place too much overemphasis on the changes wrought during the mid-sixteenth century in Europe. The number of deaths directly resulting out of Luther’s challenge to the existing Catholic order is effectively incalculable. Wars raged across Europe as secular rulers took advantage of the schisms in the religious authorities. In England, Henry VIII used the church’s difficulties to his advantage to attain the divorce he wanted and his resulting power over the church gave him the legitimacy to destroy the great abbeys and religious houses of England. This then allowed him to grab their wealth for himself and his favoured nobles.

Scotland was still a quiet backwater and though largely undisturbed by the death and destruction being raged across Europe, some of the King James V subjects were travelling to the mainland for education or for trading. Ideas have a way of acting in ways that defy the hopes and fears of those wishing to control them and the ideas of the reformation were no exception.

destruction being raged across Europe, some of the King James V subjects were travelling to the mainland for education or for trading. Ideas have a way of acting in ways that defy the hopes and fears of those wishing to control them and the ideas of the reformation were no exception.

Before long those same ideas – that the Roman church was corrupt and that it had become a wealth-seeking establishment dedicated not to promoting the glory of God, but to earthly possessions and ungodly secular power – were widespread even in quiet Scotland.

Scotland is fairly unique in Europe in that the change from Catholicism to Protestantism was relatively peaceful – at least in the body count – and can be dated almost to the year – 1560. This was the year that the a Reformation Parliament was called following the death of the Catholic Regent, Mary of Guise. Her daughter (Mary Queen of Scots) was in France having escaped the clutches of the reformers. The leader of the the Reformers was the Calvinist John Knox and it was his zeal against idolatry and against the imagined sins of the Catholic Church that set loose the mobs to sack the great medieval cathedrals and abbey churches of Scotland. This destruction led to an almost complete loss of thousands of artifacts and priceless works of art from hundreds of years of religious life in medieval Scotland.

The damage at Dunfermline was mainly to the church building itself and means that we have the spartan building that we see today. On the medieval North Entrance there are plinths and recesses clearly meant for statues. The reformers thought these were idolatrous and therefore in need of destruction. The West Door retains some carvings but the reformers did their best in their religious zeal to wipe these out as best they could.

The damage at Dunfermline was mainly to the church building itself and means that we have the spartan building that we see today. On the medieval North Entrance there are plinths and recesses clearly meant for statues. The reformers thought these were idolatrous and therefore in need of destruction. The West Door retains some carvings but the reformers did their best in their religious zeal to wipe these out as best they could.

Even though most of the stones have been weathered and defaced, you can still see some remnants of the carvings that would have graced this portal.

Though the destruction of the church was extensive: the shrine of St Margaret was destroyed, as was the high altar and the graves of the Kings that laid there; the nave was saved to act as parish church for the new Presbyterian congregation of Dunfermline. It was helped by the fact that the extensive Abbey buildings would soon be used by the wife of James VI as her Palace.

Queen Ann of Denmark rebuilt much of the abbey buildings to make a palatial building fit for her to live in away from her husband’s courts in Edinburgh and Stirling and it is this that forms the remainder of the ruins in the complex. The cloisters were demolished as was the transept and altar from the church. The Refectory and the Abbots House were linked by an arched building to allow the roadway to pass to the south. It was here that her son, the future Charles II would be born; the last monarch to be born in Scotland. It was his monarchy that would eventually lead to the period of Scottish history called The Killing Times.

for her to live in away from her husband’s courts in Edinburgh and Stirling and it is this that forms the remainder of the ruins in the complex. The cloisters were demolished as was the transept and altar from the church. The Refectory and the Abbots House were linked by an arched building to allow the roadway to pass to the south. It was here that her son, the future Charles II would be born; the last monarch to be born in Scotland. It was his monarchy that would eventually lead to the period of Scottish history called The Killing Times.

We left the Abbey at the height of Medieval Scotland with the shrine to St Margaret attracting pilgrims from across Christendom.

The Abbey became one of the most important religious sites in the country and was the burial place of many of Scotland’s kings for around 400 years. Margaret had four sons and all of them would become kings in turn until the youngest, David, could carry on the dynasty. Thereafter Most of the monarchs were interred in the Abbey Church, including Robert The Bruce.

During the wars of Independence at the end of the 13th century, the English King Edward I – Longshanks – held court in the abbey whilst on one of his regular attempts to subdue the Scots. He burned many of the buildings on leaving.

In the Abbey grounds is a small tree on a slightly raised mound. The site is supposed to be the grave of William Wallace’s mother and the legend says that returning from Dundee to Selkirk Forest, Wallace stopped here to visit the grave. He was set upon by English soldiers but managed to kill several of them and make good his escape. In the glen that runs to the south of the abbey, there is a spot known as “Wallace’s Well” were he was supposed to have hidden from pursuing soldiers.

In the Abbey grounds is a small tree on a slightly raised mound. The site is supposed to be the grave of William Wallace’s mother and the legend says that returning from Dundee to Selkirk Forest, Wallace stopped here to visit the grave. He was set upon by English soldiers but managed to kill several of them and make good his escape. In the glen that runs to the south of the abbey, there is a spot known as “Wallace’s Well” were he was supposed to have hidden from pursuing soldiers.

Unfortunately there are many legends such as these up and down the country and given the lack of any documentary or contemporary evidence, legends they must remain.

After Bruce had regained his kingdom, he specified that his heart was to be taken to fight the infidels on a crusade, whilst his body was to be interred in the traditional resting place of Kings; Dunfermline Abbey. His heart was removed from his chest and borne by

Sir James Douglas in battle against the Moors in Spain. It was retrieved after the good Sir James was killed and was brought back to be buried in Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. His body – with a sawn through rib-cage – was interred in Dunfermline.

In 1367 Robert’s great-grandson – the future Robert III – married Anabella Drummond in the Abbey and on her death and burial in 1401 a stained glass window was erected with her coat of arms.

It is around this point that the abbey reached its peak as a religious house. The church to the north of the complex, had two towers to the West which still survive largely

intact. To the south was the typical monastic buildings of a cloister and refectories used by the monkish community.

intact. To the south was the typical monastic buildings of a cloister and refectories used by the monkish community.

Benedictine monks followed the rules set out by St Benedict in the 7th century and focused on a strict hierarchy and submission to God – and by extension the church. They were self-contained communities supposed to be acting separately from wider secular society. However, given the all-pervasiveness of Roman Catholicism in the medieval world and the fact that the church was closely entwined with the monarchy, the fact was that the monasteries often acted as a secular organisation. Dunfermline for instance as noted earlier, owned the rights to the ferry at nearby Queensferry, they owned much of the land – and therefore the incomes – in West Fife and so it was obviously wealthy in its own right.

With earthly wealth comes both the potential for corruption from within and jealousy from without. The Reformation of the 16th century arrived a little late to Scotland but it swept away the monastic community in Dunfermline and its wealth was transferred to secular landowners.

I live in Dunfermline.

It’s a small town in Eastern Scotland with a long history, one which goes back over a thousand years to the very genesis of what we recognise as Scotland. It was the home, birth-place and burial-place of many of Scotland’s monarchs and and some ways echoes Scottish history in a microcosm.

Much of that history is represented in two buildings, the Abbey complex and Canmore’s Tower. Unfortunately, if the ravages of time have been unkind to the Abbey, they have nearly destroyed any remnents of the tower. It was built by Malcolm Canmore, who you may know from Shakespeare’s MacBeth and he was the ruler of a nascent Scottish kingdom in the 2nd half of the 11th century. The site is a natural fortress, being on a rocky peninsular  overlooking a steep sided ravine on three sides. The only access would have been across the narrow ridge and at the other end of this ridge, the Celtic monastary grew up. The Culdee community – as it was known as – would have been a fairly spartan group of monks and prelates, coming under the control of a Bishop and would have been the only source of literacy in the area.

overlooking a steep sided ravine on three sides. The only access would have been across the narrow ridge and at the other end of this ridge, the Celtic monastary grew up. The Culdee community – as it was known as – would have been a fairly spartan group of monks and prelates, coming under the control of a Bishop and would have been the only source of literacy in the area.

It was closely allied to the nearby Culdees in Culross – just 5 miles westward – and the island of Inchcolm – 6 miles to the east.

Inhcolm is a fascinating island; it means the Island of Colm – Colm being Columba the traditional founder of Scottish Christianity. Though there is no record of him ever visiting the island, there is evidence of some sort of religious community living there in the 6th century shortly after his death. Later, the Island monastery grew to its current size and it has survived much better than the vast majority of monastic buildings – mainly due to its island setting.

Canmore married an heiress of the English Royal family called Margaret. She had escaped England after the Norman invasion of 1066 and had been shipwrecked on the coast of Scotland. Brought before Malcolm, he instantly saw the value of marrying an English heiress and did so immediately. Though it may have been expediency, Margaret’s writings clearly show a fondness for the rough Scottish king who lived in a tower and who was just one step away from barbarity. She set about taming the man and his country. She called for Benedictine monks from Canterbury to live in the Culdee community in Dunfermline and they built a stone church for themselves and Margaret’s family. She introduced Roman rites and the English language to her husband’s court and in doing so dragged Scotland into modern medieval European life, away from the dark ages and its Celtic past.

Her sons continued this legacy, particularly David I who went in for Monastery building big-time. He founded several of them around Scotland and he commissioned the building of Dunfermline Abbey church. It is David’s building that forms the bulk of the knave today and the design owes much to Durham Cathedral in England. It is likely the architects and builders had worked on Durham before creating this smaller replica in Dunfermline.

It was the Benedictines who built up the monastery and it became a place of pilgrimage across medieval Europe. After Margaret’s death she was cannonized by the Church to become St Margaret and pilgrims coming to pray at the shrine incorperated into the high altar. Pilgrimages were lucrative businesses at that time and along with the

royal connections, the gifts of land, the monopolies on crossing the River Forth at nearby Queensferry and the ownership of mines and saltpans, the Abbey grew very wealthy. It was able to construct fantastic buildings for its community and once the secular authorities decamped for the much better defended Edinburgh and Stirling, Dunfermline became a quiet backwater – albeit a prosperous and religious one.

royal connections, the gifts of land, the monopolies on crossing the River Forth at nearby Queensferry and the ownership of mines and saltpans, the Abbey grew very wealthy. It was able to construct fantastic buildings for its community and once the secular authorities decamped for the much better defended Edinburgh and Stirling, Dunfermline became a quiet backwater – albeit a prosperous and religious one.